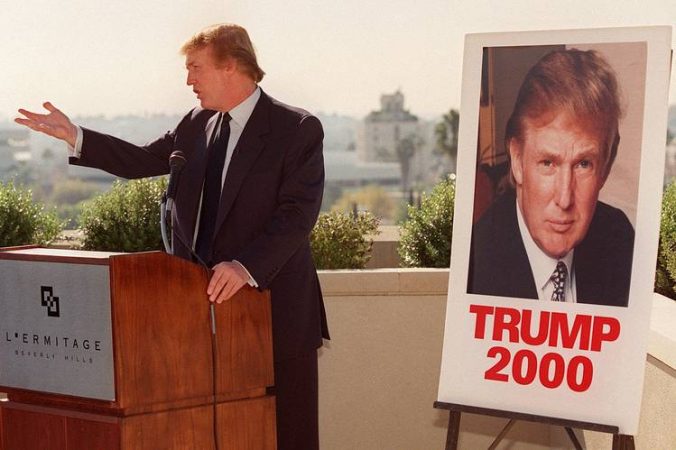

Between 1999 and 2000 I published some 40 columns on the hipster sex site, nerve.com, and in their print publication, Nerve. In the French tradition the columns fused political satire and porn. Their premise was that Kitty Lyons, a work-from-home day trader in her early thirties who shared Henry Kissinger’s conviction that “power is the ultimate aphrodisiac”, would occasionally retire to her couch to masturbate while having sex fantasies about movers and shakers in the news. Although Kitty was a fantasist, her husband, Max, was a documentary filmmaker who, as she put it, “believed in reality.” Nevertheless, she was able, on occasions such as this one, to lure him into her premise. When this piece ran, Donald Trump had left the Republican Party to explore a Reform Party bid for the White House.

Trumped Up

Original Publication date: Nov. 24, 1999

Last Wednesday, every chakra in Max’s body went chapter 11. His documentary, Homebuilding in the Heartland, was only half in the can when its German funder pulled the plug, and despite the windfall I took with 200 shares of AOL, he slid into a major droop. I tried sympathy, massage; I even sat with him through Ric Burns’ epic Donner Party, but nothing could induce the man I love to lick my wounds instead of his own.

Fantasizing about sex with a billionaire has been known to pull me through a funk; maybe it will perk up my husband, I figure. I book a room at the Plaza Hotel and tell him to meet me at 6:00 the next evening. “You must arrive as Donald Trump,” I command him, “and be prepared to rule the free world.”

Things begin well. In a blonde wig, spikes and enough mascara to tar a roof, I enter the Oak Bar feeling as mischievous as Eloise on hormones. Max arrives wearing the perfect Trump shirt: expensive and repulsive. He’s strutting with his chest puffed out, and he has combed his eyebrows up into frightened caterpillars.

In our tiny room (the best we can afford), I strip slowly, as if my body were a shady bank loan whose details it might be dangerous to fully reveal. Donald-Max lets out a whistle and tries to talk me into doing a Playboy centerfold. “Get you a million bucks American for it,” he wheedles, caressing my hip,” and I’ll only keep one third.” But like Marla, his ex, I’m obliged to decline due to deep religious and spiritual convictions.

My coy refusal (a transparent bid for a favorable pre-nup) accompanied by the sort of sultry pout that assures a man you love him primarily for his liquid assets, makes Max feel all mogul-like. His manhood skyrockets in value, burgeoning instantly from indebted worm to $9.2-billion-dollar Reform Party Contender.

I grab his handle as if he was my lucky slot machine, then go down on him like a pro, without the preliminary licks or sniffs that normally make it fun for me. Now that my husband’s a greedy go-getter worth billions, it gets me hot anyway.

“Fund me now,” he cries, and proceeds to excavate my foundation.

“I’m going to make Mike Tyson Secretary of State,” he pants. “I’ll meet with Arafat at Wrestlemania. Subsidize plastic surgery for the ugly and uninsured. Reporters who don’t like it will get audited.”

No sooner do I begin to congratulate myself on coming up with this clever scheme, when Max enters turn-off territory.

“I want a divorce,” he continues, “so I can bed every good-looking babe on the Elite Modeling Agency roster, except, of course, my daughter, whom I must by law bequeath to another billionaire to marry and dump when she gets old enough to have a brain.”

All of a sudden this fuck is starting to feel like one of those bright ideas that, once begun, drag on for dismal eons — like The Blair Witch Project or the House of Lords. I fake a few moans to hurry him up, ready to settle for what Marla got (about .001%) and bail the hell out.

Maybe Max can tell, because all of a sudden he breaks character completely. The way he calls out for Kitty, his intensity and the need I feel in him make giddy sensations spin through my tits and twat like roulette balls. Casino lights flash in my blood and my clit tingles like a gambler on a roll. By the time Max’s newfound confidence spurts forth, I’m wet enough to . . . to . . . Soak the Rich!

Afterwards, the latest Trump campaign slogan hovering in my post-coital mind, I can practically hear my mother lecturing about how Trump is the only candidate who addresses the problem of income disparity. Thanks, Mom, but I’ve learned more than enough about Trump from sleeping with my husband. For me, The Donald was only truly sexy before his famous Comeback, when he was down, in doubt and in love, when the swell of his desire was pressed against the locked doors of edifices he himself had erected, when he was raining flop sweat and looking up the skirt of fortune, begging her for one more taste. Cocky and on top of his world he gives off all the emotional complexity of a gold brick.

I’m just about to tell Max how much I prefer his own student-loan-afflicted self when he preempts me.

“I’m not Donald Trump anymore,” he declares.

“Good Boy!” I exclaim supportively.

“I’m Steve Forbes!”

I beat him with my wig until he agrees to drop out of the race.

Here’s a piece on the fabulous Carson brothers I did for T Mag blog…I called it “Here’s Looking At You Kids” but they retitled it “

Here’s a piece on the fabulous Carson brothers I did for T Mag blog…I called it “Here’s Looking At You Kids” but they retitled it “

Stay tuned for samples of Maggie Cutler’s columns from nerve.com: “The Secret Life of Kitty Lyons,” a series of political sex fantasies from the Clinton era.

Stay tuned for samples of Maggie Cutler’s columns from nerve.com: “The Secret Life of Kitty Lyons,” a series of political sex fantasies from the Clinton era.