Titled “Heaven Can Wait,” From The Downtown Express, column, “The Big Idea by Lynn Phillips” November 7th, 1990

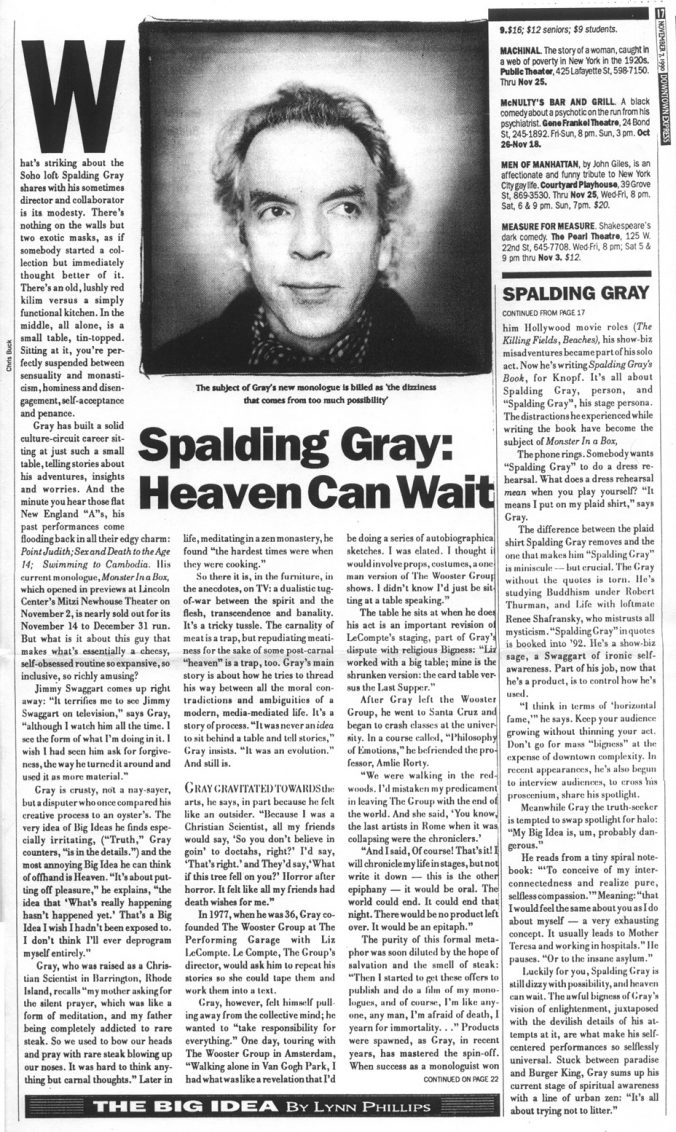

What’s striking about the Soho loft Spalding Gray shares with his sometime director and collaborator is its modesty. There’s nothing on the walls but two exotic masks, as if somebody started a collection but immediately thought better of it. There’s an old, lushly red kilim versus a simply functional kitchen. In the middle, all alone, is a small table, tin-topped. Sitting at it, you’re perfectly suspended between sensuality and monasticism, hominess and disengagement, self-acceptance and penance.

Gray has built a solid culture-circuit career sitting at just such a small table, telling stories about his adventures, insights and worries. And the minute you hear those flat New England “A”s, his past performances come flooding back in all their edgy charm: Point Judith; Sex and Death to the Age

14; Swimming lo Cambodia. His current monologue, Monster in a Box, which opened in previews at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi Newhouse Theater on November 2, is nearly sold out for its November 14 to December 31 run. But what is it about this guy that makes what’s intially a cheesy, self-obsessed routine so expansive, so inclusive, so richly amusing?

Jimmy Swaggart comes up right away: ”It terrifies me to see Jimmy Swaggart on television,” says Gray, “although l watch him all the time. I see the form of what l’m doing in it. I wish I had seen him ask for forgiveness, the way he turned it around and used it us more material.”

Gray is crusty, not a nay-sayer, but a disputer who once compared his creative process to an oyster’s. The very idea of Big Ideas be finds especially irritating, (“Truth,” Gray counters, “is in the details.”) and the most annoying Big Idea be can think of offhand is Heaven. “It’s about putting off pleasure,” he explains, “the idea that ‘What’s really happening hasn’t happened yet.’ That’s a Big Idea I wish I hadn’t been exposed to. I don’t think I’ll ever deprogram myself entirely.”

Gray, who was raised os a Christian Scientist in Barrington, Rhode Island, recalls “my mother asking for the silent prayer, which was like a form of meditation, and my father being completely addicted to rare steak. So we used to bow our heads and pray with rare steak blowing up our noses. It was hard to think anything but carnal thoughts.” Later in life, meditating in a zen monastery, he found “the hardest times were when they were cooking.”

So there it is, in the furniture, in the anecdotes, on TV: a dualistic tug-of-war between the spirit and the flesh, transcendence and banality. It’s a tricky tussle. The carnality of meat is a trap, but repudiating meatiness for the sake of some post-carnal “heaven” is a trap, too. Gray’s main story is about how he tries to thread his way between all the moral contradictions and ambiguities of a modern, media-mediated life. It’s a story of process. “It was never an idea to sit behind a table and tell stories,” Gray insists. “It was an evolution.” And still is.

Gray gravitated towards the arts, he says, in part because he felt like an outsider. “Because I was a Christian Scientist, all my friends would say, ‘So you don’t believe in goin’ to doctahs, right?’ I’d say,

‘That’s right.’ and They’d say, ‘What if this tree fell on you?’ Horror after horror. It felt like all my friends had death wishes for me.”

In 1977, when he was 36, Gray co-founded The Wooster Group at The Performing Garage with Liz LeCompte. LeCompte, The Group’s director, would ask him to repeat his stories so she could tape them and work them into a text.

Gray, however, felt himself pulling away from the collective mind; he wanted to “take responsibility for everything.” One day, touring with The Wooster Croup in Amsterdam, “Walking alone in Van Gogh Park, I had what was like a revelation that I’d be doing a series of autobiographical sketches. l was elated. I thought it would involve props, costumes, a one man version of The Wooster Group shows I didn’t know I’d just be sitting at a table speaking.”

The table he sits at when he does his act is an important revision of LeCompte’s staging, part of Gray’s dispute with religious Bigness: “Liz worked with a big table; mine is the shrunken version: the card table version of the Last Supper”

After Gray left the Wooster Group, he went to Santa Cruz and began to crash classes at the university. ln a course called, “Philosophy of Emotions,” he befriended the professor, Amlie Rorty.

“We were walking in the redwoods. I’d mistaken my predicament with leaving the The Group with the end of the world. And she said, ‘You know, the last artists in Rome when it was collapsing were the chroniclers.’

“And I said, Of course! That’s it! I will chronicle my life in stages, but not write it down—this is the other epiphany – it would be oral. The world could end. It could end that night. There would be no product left over. It would be an epitaph.”

The purity of this formal metaphor was soon diluted by the hope of salvation and the smell of steak: “Then I started to get these offers to publish and do a film of my monologues, and of course, I’m like anyone, any man, I’m afraid of death, I yearn for immortality…” Products were spawned, as Gray, in recent years, has mastered the spin-off. When success as a monologuist won him Hollywood movie roles (The Killing Fields, Beaches), his show-biz misadventures became part of his act. Now he’s writing Spalding Gray’s Book, for Knopf. It’s all about Spalding Gray, person, and “Spalding Gray”, his stage persona. The distractions he experienced while writing the book have become the subject of Monster in a Box.

The phone rings. Somebody wants “Spalding Gray” to do a dress rehearsal. What does a dress rehearsal mean when you play yourself? “It means I put on my plaid shirt,” says Gray.

The difference between the plaid shirt Spalding Gray removes and the one that makes him “Spalding Gray” is miniscule—but crucial. The Gray without the quotes is torn. He’s studying Buddhism under Robert Thruman, and Life with loftmate Renee Shafransky, who mistrusts all mysticism. “Spalding Gray” in quotes is booked into ’92. He’s a show-biz sage, a Swaggart of ironic self-awareness. Part of his job, now that he’s a product, is to control how he’s used.

“I think in terms of ‘horizontal fame,’ he says. Keep your audience growing without thinning your act. Don’t go for mass “bigness” at the expense of downtown complexity. In recent appearances, he’s also begun to interview audiences, to cross his proscenium, share his spotlight.

Meanwhile Gray the truth-seeker is tempted to swap spotlight for halo: “My Big Idea is, um, probably dangerous.”

He reads from a tiny spiral notebook: “‘To conceive of my inter-connectedness and realize pure, selfless compassion.”‘ Meaning: “that I would feel the same about you as I do about myself — a very exhausting concept. It usually leads to Mother Teresa and working in hospitals.” He pauses. “Or to the insane asylum.”

Luckily for you, Spalding Gray is still dizzy with possibility, and heaven can wait. The awful bigness of Gray’s vision of enlightenment, juxtaposed with the devilish details of his attempts at it, are what makes his self-centered performances so selflessly universal. Stuck between paradise and Burger King, Gray sums up his current stage of spiritual awareness with a line of urban zen: “It’s all about trying not to litter.”

Why read it? My editor at The Downtown Express was Jan Hodenfield. Years after Gray’s terrible death in 2004 Jan called to tell me he’d reread this interview and it remained his favorite piece of mine and also his favorite piece on Gray, In the light of subsequent events, the themes it strums and conflicts it delineates are really haunting.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.